Few artists transform our understanding of the world, and fewer still do so by delving into the abstract qualities of light and atmosphere. One such visionary was Claude Monet, whose fog-shrouded paintings of London, created during three visits between 1899 and 1901, reshaped how the city was perceived—both by its residents and by the world. A new exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery, Monet and London: Views of the Thames, charts this groundbreaking series and how it altered London’s self-image forever.

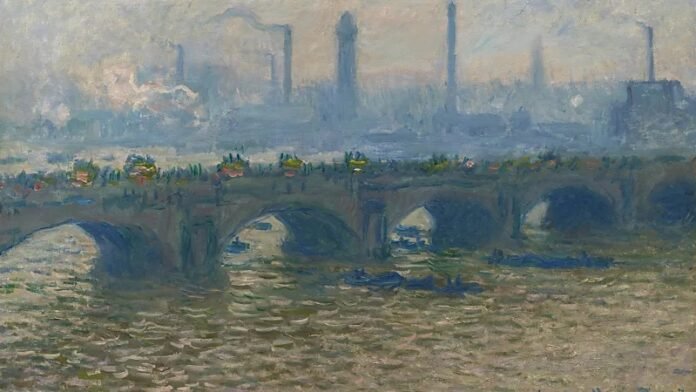

Monet’s revolutionary depictions of the Thames, with its iconic landmarks shrouded in vaporous fog, captured the ethereal essence of London. These nearly 100 paintings—more than he dedicated to any other subject—would forever redefine the “unreal city,” as poet T.S. Eliot would later describe it. Rather than simply documenting the urban landscape, Monet was crafting optical experiments, exploring how light itself could dissolve the material world into something both transient and infinite.

One of the most famous works from the series, London, The Houses of Parliament, Shaft of Sunlight in the Fog, epitomizes Monet’s mastery. Painted during his second London stay in 1901, the canvas depicts the towers of the Palace of Westminster faintly shimmering through a veil of late-afternoon sun, partially obscured by fog. From his vantage point at St. Thomas’s Hospital on the Southbank, Monet captured the fluctuating interplay between fog, sunlight, and architecture. The result is a dreamlike vision where form becomes elusive, constantly on the verge of disappearing into light.

Unlike his earlier peers in Impressionism, Monet wasn’t content to simply portray the effects of light. His paintings go further, suggesting that light and air possess the power to transform and obliterate form altogether. In Monet’s London works, even the most permanent structures—bridges, palaces—appear to fight for their survival against the forces of nature. His canvases blur the lines between solid and ethereal, challenging the viewer to reimagine the world as a series of luminous veils rather than static forms.

This approach was so radical that it left many early observers confounded. American collector Desmond FitzGerald, upon viewing the paintings, described them as retinal riddles: “At first the beholder gazes with astonishment at what seems to be a half-finished picture; but gradually, as the eye penetrates the fog, objects begin to come out… The illusion is wonderful, and has never been attempted in exactly the same manner before.” Monet’s mastery lay in creating this illusion of objects dissolving and re-emerging from the fog, a visual paradox that was unprecedented in art history.

Monet himself understood that his vision of London depended on its most characteristic and elusive element—fog. “Without the fog,” he famously remarked, “London wouldn’t be a beautiful city. It’s the fog that gives it its magnificent breadth.” On mornings when the air was too clear, Monet panicked, fearing that his canvases would be ruined by the absence of mist. He wasn’t interested in painting the city as it appeared, but rather in capturing the mysterious, intangible atmosphere that made it so haunting.

The timing of Monet’s London series coincides with a significant breakthrough in the scientific understanding of light. At the same time Monet was experimenting with the way light fragmented and dispersed across his canvases, physicist Max Planck was laying the groundwork for quantum theory, describing light as packets of energy, or quanta. Light, both in art and science, was being redefined. Monet’s Thames paintings thus stand as both artistic and scientific milestones, offering a pioneering exploration of how light behaves in the natural world.

Oscar Wilde, writing at the same time that Monet was creating his London works, echoed this transformation of perception in his essay The Decay of Lying. Wilde argued that London’s fog had always existed, but it wasn’t until artists and poets captured its beauty that people began to truly see it. Monet’s works make this idea tangible: “Things are because we see them,” Wilde wrote, “and what we see, and how we see it, depends on the Arts that have influenced us.” Monet’s fog-drenched visions would forever alter how Londoners viewed their own city.

By the turn of the century, London was an industrial powerhouse, its skies thick with soot and smog from factories. While other artists, such as J.M.W. Turner, had depicted this industrial pollution as a stain on the landscape, Monet saw something entirely different. To him, the smoke and mist were a revelation—a way to transcend the physical world and explore the deeper mysteries of light and perception.

The exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery offers a rare opportunity to see a significant number of these works reunited. It showcases the immersive, transformative power of Monet’s vision—an audacious attempt to capture the ephemeral beauty of a city in flux. Over four years, Monet continually revised his paintings, layering them with the fleeting impressions of light and fog. The final results are masterpieces of atmospheric beauty that, more than a century later, still mesmerize viewers.

Monet and London: Views of the Thames is a testament to how art can reshape our understanding of place. It invites us to see London not as a fixed, concrete city, but as an ever-shifting, mesmerizing mirage—an idea that continues to inspire and captivate. The exhibition runs at the Courtauld Gallery, London, until January 19, 2025.