Long before pipelines, water meters, and concrete dams, the people of ancient India were building water systems that were as beautiful as they were brilliant. Across the subcontinent, civilizations carved aquifers into stone, channeled rain from temple rooftops, and turned public squares into reservoirs. These weren’t just feats of engineering — they were communal, cultural, and ecological masterpieces.

From the gridded perfection of Mohenjo-daro to the mesmerizing geometry of Rajasthan’s stepwells, India’s ancient water systems reveal a truth that feels more relevant than ever today: sustainability doesn’t have to be modern. It just has to be wise.

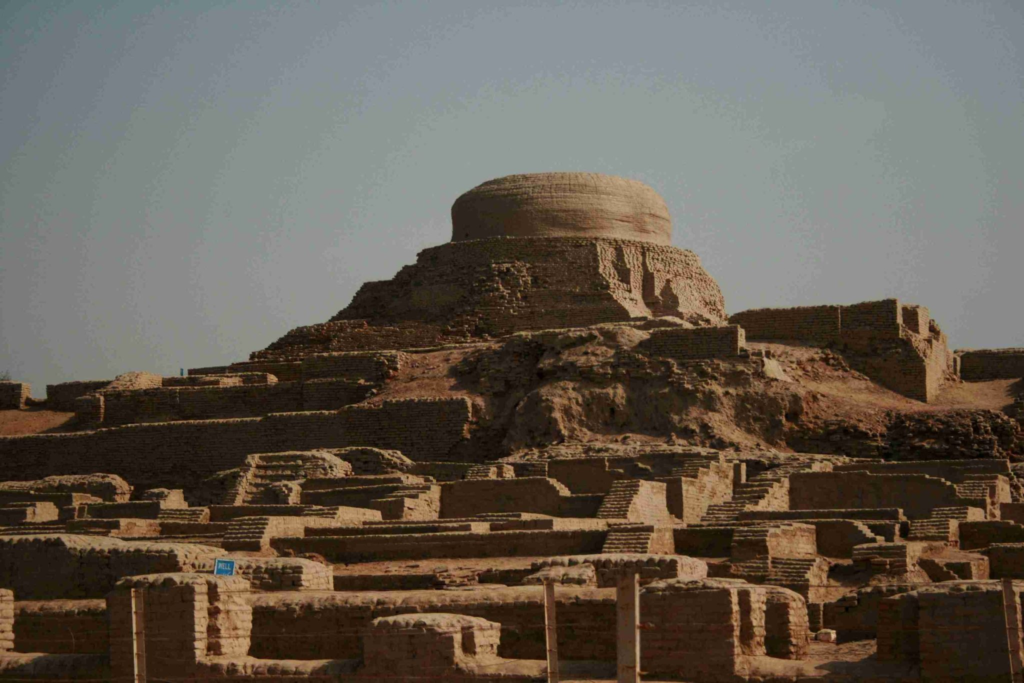

Mohenjo-daro: The Blueprint City

Travel back to around 2500 BCE, and you’ll find yourself walking through the eerily advanced streets of Mohenjo-daro, one of the crown jewels of the Indus Valley Civilization. What strikes you isn’t just the grid layout or the uniform brick houses — it’s the plumbing.

Every house had access to a private well. Bathing areas were neatly designed, and wastewater was directed through a network of covered drains that led out to the city’s larger drainage system. Hygiene, urban planning, and civic sense — all in a city over 4,000 years old.

Mohenjo-daro wasn’t just ahead of its time — it might still be ahead of ours.

Chand Baori: The Desert’s Geometric Heart

In the sun-scorched plains of Rajasthan, where every drop of water is worth its weight in gold, ancient builders carved a solution deep into the earth.

Chand Baori, in the village of Abhaneri, is a marvel — 3,500 perfectly symmetrical steps descend over 13 stories, creating a labyrinthine pattern that could hypnotize a drone. But this wasn’t just an aesthetic flex. The stepwell harvested rainwater and kept it cool — offering a temperature drop of several degrees, even in peak summer.

It was also a community hub, where people gathered not just to draw water, but to find shade, share stories, and celebrate rituals. Water, here, was not just a resource — it was a reason to come together.

Rani ki Vav: A Temple to Water

Move west to Gujarat, and water becomes sacred sculpture.

Rani ki Vav — the Queen’s Stepwell in Patan — is a subterranean wonder built in the 11th century by Queen Udayamati in memory of her husband, King Bhima I. Today, it stands as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. But long before the plaques and cameras, it stood as a fusion of devotion, art, and ecological foresight.

Over 500 intricately carved deities line its sandstone walls. Yet beneath the beauty lay function: the well not only stored water but helped recharge groundwater — a clever adaptation to Gujarat’s dry climate.

Here, engineering met mythology. Science met soul.

Temple Tanks: Where the Sacred Meets the Sustainable

In the temple towns of South India — Madurai, Kanchipuram, Thanjavur — water found yet another form: the temple tank.

Known as pushkarinis or kunds, these tanks were ritualistic spaces where pilgrims bathed before entering temples. But they were also practical — designed to capture monsoon rains and recharge aquifers. The golden lotus tank of Meenakshi Temple in Madurai is not just a serene sight — it’s a living water system, quietly serving the city through centuries.

Here, spiritual purity and environmental purity were one and the same.

Toorji Ka Jhalra and the Culture of Conservation

Built in the 1740s in Jodhpur, Toorji Ka Jhalra is a stepwell that exemplifies another key aspect of ancient water systems — community investment.

Funded by royal women and wealthy patrons, many of these water structures weren’t just charity projects. They were legacies. Statements of civic duty. Gifts to the future. And they weren’t hidden behind gates — they were shared spaces. Women washed clothes, children played, elders gathered under shade.

Water wasn’t just managed. It was celebrated.

From Decline to Revival

Then came colonial systems, pipelines, and the convenience of taps — and with them, a slow decline. Many traditional water structures were neglected, covered up, or allowed to fall into disrepair. Cities grew. Attention shifted. The ancient wisdom was buried.

But now, in the face of climate change, droughts, and urban water shortages, these old systems are being looked at with fresh eyes. Conservationists are restoring stepwells. Planners are studying traditional rainwater harvesting. Citizens are rallying to bring the old ways back — not out of nostalgia, but out of necessity.

Lessons for Today’s Thirsty Cities

What made ancient India’s water management so powerful wasn’t just clever engineering. It was integration.

Water was a community experience, a cultural priority, and a climate-adaptive practice. It was decentralized and democratic. The systems weren’t imposed from above — they were built into the rhythms of everyday life.

As modern cities battle water crises and ecological imbalance, perhaps the future lies in the past. These ancient technologies weren’t primitive. They were precise. Thoughtful. And sustainable.

By reviving and adapting them, we’re not just conserving heritage — we’re designing a future that listens to the land, respects the seasons, and values water not just as a utility, but as life itself.

Because in India, water was never just about survival. It was always about connection.