In the Shivpuri district of Madhya Pradesh, a deeply unsettling practice known as “Dhadeecha Pratha” continues to haunt the region. This exploitative ritual allows men to “buy” or “rent” women through formal agreements written on a mere Rs. 10 stamp paper. Economic hardship and the societal burden of dowries have led families to offer their daughters or wives in this dehumanizing trade. The practice, shrouded in cultural and economic despair, underscores the grim reality faced by women in the region.

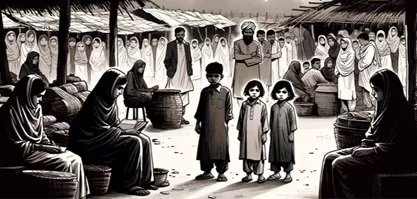

The annual market event, a scene of unthinkable transactions, sees young girls—some as young as 8 to 15 years old—put on display for men to select. Prices range from Rs. 15,000 to Rs. 25,000, with higher amounts, even reaching Rs. 2 lakh, demanded for girls considered more attractive or virginal. These agreements, shockingly formalized through stamp paper contracts, bind the girls into periods of “rent” that can last from hours to several years, depending on the payment.

Across India, women involved in such arrangements are often referred to as “Paro” or “Molki,” terms that chillingly translate to “those who have a price.” Virgin girls are particularly sought after, with their perceived purity fetching exorbitant amounts. Meanwhile, non-virgin women and older girls are rented out for lesser sums, with their value assessed on factors such as skin tone, age, and marital history. In some cases, husbands exploit this system further by selling or renting out their wives to supplement their income.

Despite efforts by NGOs and activists to combat this practice, Dhadeecha Pratha persists, fueled by economic desperation, lack of education, and deeply ingrained patriarchal norms. The cycle of exploitation continues, perpetuated by poverty and societal indifference. The plight of these women is a stark reminder of the urgent need for systemic change.

The horrors of Dhadeecha Pratha echo similar practices globally, where women are commodified under the guise of tradition or necessity. In 2006, a man in Gujarat infamously rented out his wife for Rs. 8,000 a month to a businessman. In parts of Africa, practices like “Leblouh” in Mauritania force girls as young as eight into early marriages. These global parallels highlight the pervasive nature of gender-based exploitation and the shared responsibility to address it.

Ending practices like Dhadeecha Pratha requires a multi-faceted approach: addressing the root causes of poverty, promoting education, and empowering women through sustainable livelihood opportunities. Community outreach and stricter enforcement of laws protecting women’s rights are crucial. While the road to eradicating such practices is long, collective action can pave the way for a future where women are no longer commodities but individuals with dignity and rights.