US scientists have made a bold claim: they are attempting to build the world’s first experiment specifically designed to detect a single graviton — the hypothetical quantum particle believed to carry gravity. The project, which has secured $1.3 million in funding, has sparked excitement as well as deep scepticism within the physics community, reviving a decades-old debate over whether gravitons can ever be observed — and whether their detection would finally prove that gravity is quantum in nature.

What Is the Proposed Experiment?

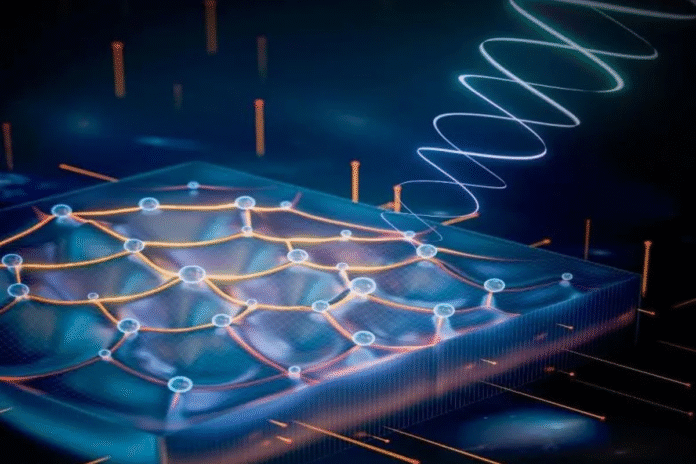

The experiment is being developed by researchers at the Stevens Institute of Technology in collaboration with Yale University. Their approach involves an ultra-sensitive detector built around a cylindrical resonator filled with superfluid helium — a rare state of matter that behaves as a single quantum system when cooled to near absolute zero.

The detector would be cooled to its quantum ground state, eliminating thermal noise. In this ultra-quiet environment, scientists hope to “listen” for an extremely faint disturbance. If a powerful gravitational wave — such as one produced by merging black holes — passes through the detector, theory suggests it could deposit a single quantum of energy into the helium. This energy would appear as a tiny mechanical vibration, known as a phonon, which could be detected using precision lasers.

Project co-leader Igor Pikovski has clarified that the three-year project is unlikely to detect a single graviton immediately. Instead, the goal is to demonstrate a working prototype that future experiments could refine.

Why Does the Graviton Matter?

In modern physics, forces are carried by particles: photons for electromagnetism, and other particles for the strong and weak nuclear forces. Gravity, however, is described by Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity as the curvature of spacetime — not as a particle-based force.

Physicists have long suspected that gravity, too, has a quantum carrier: the graviton. Confirming its existence would help bridge the gap between general relativity, which governs stars and galaxies, and quantum mechanics, which governs atoms and subatomic particles. Detecting a graviton would represent a crucial step toward a long-sought unified “theory of everything.”

Gravitational waves — first detected in 2015 by observatories such as LIGO — are often described as ripples in spacetime. Scientists believe these waves may consist of enormous numbers of gravitons acting together, but no experiment has ever isolated even one.

Why Has Detecting a Graviton Been Considered Impossible?

The primary challenge is gravity’s extreme weakness. Compared to electromagnetism, gravity is about 10³⁶ times weaker. A simple fridge magnet can overpower the Earth’s gravitational pull on a paperclip — a commonly cited illustration of gravity’s relative weakness.

In a widely cited 2006 analysis, physicists Tony Rothman and Stephen Boughn concluded that a detector capable of reliably detecting a single graviton would need to be impossibly massive — roughly the mass of Jupiter — and placed near an intense source such as a neutron star. Even then, it might detect only one graviton every ten years.

Moreover, shielding such a massive detector from background particles like neutrinos would require so much material that the detector itself would collapse into a black hole. Their conclusion was stark: a graviton detector large enough to work cannot physically exist.

How Does the New Proposal Challenge This View?

The Stevens–Yale team argues that previous calculations assume gravitons must be detected by directly absorbing them — similar to a particle striking a detector. Instead, the new proposal relies on resonance, comparable to how an opera singer can shatter a wine glass by matching its natural frequency.

By exploiting quantum resonance effects rather than brute-force absorption, the researchers believe it may be possible — at least in principle — to sense the faintest quantum signature of gravity without requiring an impossibly massive detector.

Whether the experiment succeeds remains uncertain, but its ambition has already reignited one of physics’ most fundamental debates: is gravity truly quantum, and can humanity ever prove it?