Few dishes in India inspire as much emotion, loyalty and debate as biryani. It is not just food, it is geography on a plate, history layered in rice and spice, and memory sealed with aroma. The map of biryani variants across the subcontinent proves one simple truth: there is no single biryani, only many stories sharing one name.

The roots of biryani are believed to trace back to the Persian words birian meaning fried before cooking or birinj meaning rice. As the dish travelled through royal kitchens, trade routes and home hearths, it adapted, absorbed and transformed. What emerged was not imitation but identity, shaped deeply by local ingredients, cooking methods and cultural habits.

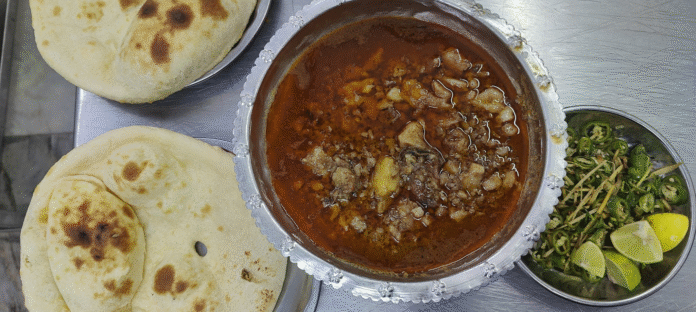

In the north, Awadhi or Lucknowi biryani reflects royal restraint and finesse. Long grained basmati rice, tender meat and whole spices are cooked slowly using the dum method, allowing flavours to gently infuse without overpowering each other. Saffron, kewra water and rose essence add fragrance, while the absence of excessive chillies highlights balance over heat. Moradabadi biryani, in contrast, is robust and straightforward. Known for its generous portions of meat, mild spices and quick cooking style, it is often eaten fresh off the pot with chopped onions and green chillies, making it a favourite at roadside stalls and community feasts.

Move east and Kolkata biryani tells a story of adaptation and elegance. Introduced by the Nawabs of Awadh during a time of economic hardship, the addition of potatoes was born out of necessity but became iconic. Lightly spiced with nutmeg and aromatic rice, it focuses on subtle sweetness and aroma rather than richness. The boiled egg, another signature element, adds texture and has become inseparable from the city’s biryani identity.

The western belt offers bold contrasts and unapologetic flavours. Sindhi biryani is fiery, tangy and layered with tomatoes, yoghurt and green chillies, making every bite intense and vibrant. Memoni biryani, influenced by Gujarati and Middle Eastern spices, is equally spicy but richer, often cooked with slow-simmered meat and deep masalas. Bombay biryani reflects the city’s love for layered tastes, combining sweetness from dried plums, heat from spices and fried potatoes that soak up the gravy. Along the coast, Bhakali and Beary biryanis use local rice varieties, coconut based spice blends and seafood or meat, grounding the dish firmly in regional, home-style cooking traditions.

Down south, biryani takes on even more personality. Ambur and Arcot biryanis from Tamil Nadu rely on short grain rice and a sharp, chilli-forward masala, cooked quickly to lock in bold flavours. Chettinad biryani stands out for its use of black pepper, fennel and local spices, giving it a deep, earthy heat that lingers. In Kerala, Malabar and Thalassery biryanis offer a gentler experience. Cooked with fragrant jeerakasala rice, ghee and mild spices, they focus on aroma and richness, often paired with dates pickle and raita to balance flavours.

Then there is Kacchi biryani, a test of true skill. Here, raw marinated meat is layered with partially cooked rice and sealed for slow dum cooking. As everything cooks together, the meat releases its juices into the rice, creating unmatched depth of flavour. It demands precision, timing and experience, making it as much craft as cuisine.

What makes this journey even more fascinating is how deeply biryani is woven into modern life. Despite evolving food trends and global influences, biryani continues to dominate food delivery charts, with millions of orders placed every year and several plates being served every second.

The biryani trail is not about deciding which version is superior. It is about understanding how one dish became a cultural mirror. Every biryani carries the climate, history and temperament of its region. Together, they form a map not just of flavours, but of India itself.